Spring Framework 7 and Spring Boot 4: The tastiest bites - JVM Weekly vol. 153

What new Spring brings to the table!

I know I usually don’t write about new releases outside of “Rest of the Story”, but hey - this is a major Spring release, so…

This week, Spring (according to their calendar) released a new generation of practically all its flagship projects: Spring Framework 7, Spring Boot 4, Spring Data 2025.1, and a release for Spring AI 1.1 for the Boot 3.5 line (while actively developing 2.x for Spring Boot 4).

Let’s be honest - major version bumps like these don’t just happen “by the way.” They usually mark the end of an era rather than just another patch. New Spring fits into a much broader shift across the entire ecosystem. Java has racked up new LTS releases, Jakarta EE has finally closed the book on the javax to jakarta migration, GraalVM stopped being just a “conference talk curiosity,” and AI has moved from hackathons straight into budgets, roadmaps, and KPIs.

But here’s the thing: Spring isn’t just trying to keep up - it clearly wants to co-define this movement.

That’s why, instead of throwing in yet another “compatibility flag” or one more section in application.yml, the team decided to go for a coordinated, one-time “Big Bang.” In this release, the foundations have been aligned with new standards, a massive chunk of technical debt has been paid off, and the platform has been positioned for the AI-driven years ahead. From the outside, it looks like a version migration. From the inside? It looks like a redesign of Spring’s entire mental model.

The foundation: goodbye javax

At the fundamental level, the changes are very concrete. The world of javax officially disappears from the main path. Annotations like @Resource, @PostConstruct, or @Inject - present in almost every project for years - need to be migrated to the new path.

import javax.annotation.PostConstruct;

import javax.persistence.Entity;

@Entity

public class LegacyUser {

@PostConstruct

private void init() { ... }

}They are now moved to a consistent, Jakarta-native world compliant with Jakarta EE 11.

import jakarta.annotation.PostConstruct;

import jakarta.persistence.Entity;

@Entity

public class ModernUser {

@PostConstruct

private void init() { ... }

}But there is another “hidden landmine” in the plumbing: Jackson 3. Just like the Jakarta migration, the new Jackson version changes package names. Spring Framework 7 is doing some heavy lifting to support a mix of Jackson 2 and 3 for now, but the signal is clear: the old JSON backend is on its way out, and we are looking at another ecosystem-wide shift.

At the same time, the entire stack gets a lift: newer Servlet, JPA, Bean Validation, plus new generations of Tomcat and Jetty. Some well-known servers, like Undertow, simply didn’t make the cut for the new standard and have dropped out of the Spring ecosystem. It hurts (I remember using Undertow regularly back in my Clojure days), but it closes a chapter. This leap had to happen - the only question was whether it would be a single, planned surgical cut, or a “death by a thousand cuts” via endless, frustrating compatibility fractures. Spring chose option one.

The Billion Dollar Mistake and other improvements for sanity sake

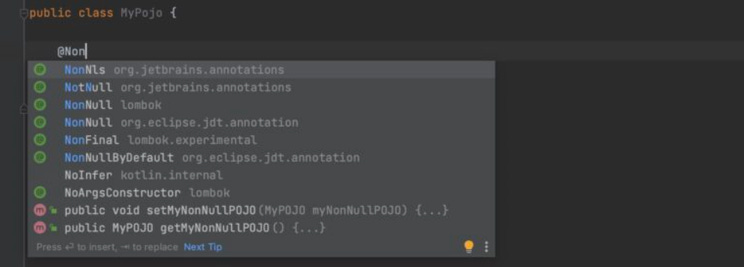

The second axis of change concerns the daily developer experience. It starts with something we all know a little too well: nulls. Spring Framework 7 and the new generation of libraries around it (Spring Data, Spring Security, Spring Vault) adopt JSpecify.

To understand why this is huge, you have to remember the absolute mess we’ve lived in for the last 15 years. We had javax.annotation.Nullable, org.jetbrains.annotations.Nullable, edu.umd.cs.findbugs.annotations.Nullable, and android.support.annotation.Nullable. It was the Wild West, where tools (IDEs, Sonar) often ignored each other’s annotations.

JSpecify is the peace treaty. It is a standard agreed upon by the giants (Google, JetBrains, Oracle, and others) to finally speak one common language about nullability.

In Spring Framework 7, this manifests as a massive “Inversion of Control” for nulls. Thanks to the @NullMarked annotation applied at the package level, Spring stops being “everything can be null” by default. instead, it sends a clear signal: non-null is the normal case. You no longer have to clutter your code with @NonNull on every parameter. You only explicitly mark the exceptions with @Nullable.

@org.jspecify.annotations.NullMarked

package com.example.billing;

public class BillingService {

// The compiler knows ‘invoice’ cannot be null.

public Receipt processPayment(Invoice invoice) {

return new Receipt(invoice.getId());

}

public @Nullable Transaction findHistory(@Nullable String transactionId) {

return transactionId != null ? repo.find(transactionId) : null;

}

}We can expect stop of the “hacky workarounds” we’ve been doing for a decade.

First, API Versioning is finally a first-class citizen. No more writing custom interceptors or dragging in external libraries just to version your REST endpoints. Whether you prefer path-based, header-based, or query-param versioning, it is now supported natively by standard annotations.

@RestController

@RequestMapping(”/orders”)

public class OrderController {

// Native API Versioning support (Header, Path, or Param)

// No more custom interceptors needed

@GetMapping

@ApiVersion(value = “1.0”, strategy = VersionStrategy.HEADER)

public List<Order> getOrdersLegacy() {

return repository.findAll();

}

// Resilience patterns moved directly into Core

// No extra ‘spring-retry’ dependency required

@Retryable(maxAttempts = 3, backoff = @Backoff(delay = 500))

@GetMapping

@ApiVersion(value = “2.0”, strategy = VersionStrategy.HEADER)

public List<Order> getOrdersResilient() {

return service.fetchOrdersWithRateLimit();

}

}Second, Resilience patterns (Retries, Circuit Breakers, Rate Limiters) are being moved/promoted directly into spring-core and the main framework. Features like @Retryable and Rate Limiting have moved directly into spring-core. You no longer need to pull in extra dependencies or rely solely on external tools like Resilience4j for basic robustness. In distributed system failures are a default state (I hope everybody internalized that knowledge by now) and the framework finally treats them that way “out of the box.”

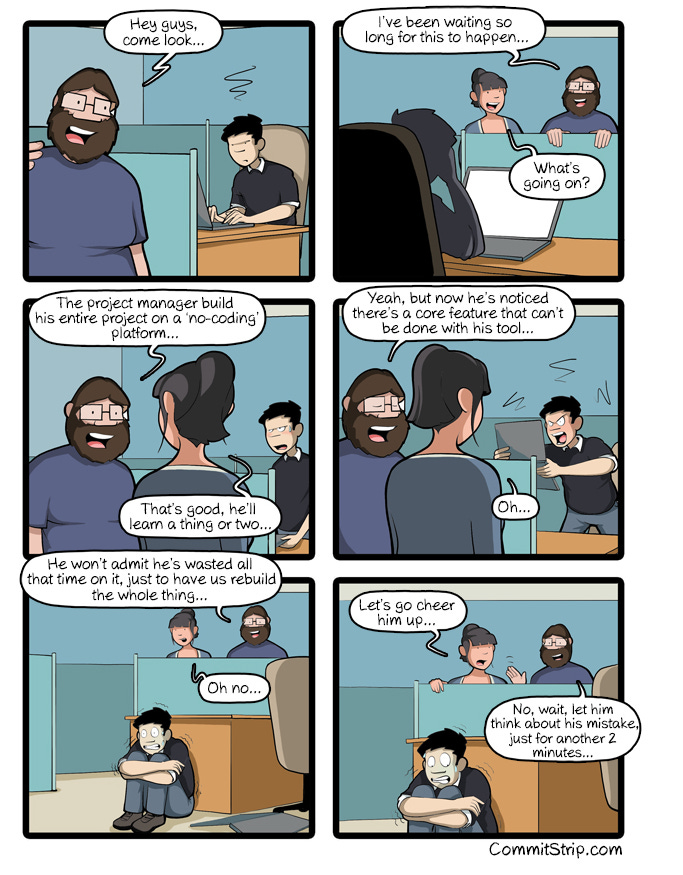

Less magic, more build-time actions

The third axis is Spring’s relationship with the compiler and the build process. For years, Spring was the master of “runtime magic”: classpath scanning, dynamic configuration, reflection, proxies. This gave us incredible flexibility, but it came with consequences. On one hand, we always dealt with technology indistinguishable from magic (cheers to Arthur C. Clarke), but on the other, in the era of containers, cold starts, and native images, it started to hurt.

The new Spring - following the current fashion in the ecosystem - consistently shifts the workload to build time. Instead of doing “everything” at startup, it tries to know and generate as much as possible beforehand.

You can see this best in Spring Boot 4. The existing spring-boot-autoconfigure, which bloated over the years, has been broken down into a neat set of smaller modules. Suddenly, your IDE stops flooding you with suggestions for classes and configuration properties that aren’t even on your classpath. And this is exactly where the Spring AOT world meets what’s happening inside the Virtual Machine itself within Project Leyden.

Leyden in OpenJDK has the exact same goal, just a level lower: improve startup time, time-to-peak performance, and application footprint by shifting as much work as possible from execution time to an earlier stage. JDK 24 brought the first installment of this philosophy with JEP 483: Ahead-of-Time Class Loading & Linking, which can load and link classes during a “training” run and save the result in a special cache.

So when you combine this with modular Boot 4 and Spring AOT, the puzzle starts to come together. By slicing up autoconfiguration and moving “magic” parts to code generated at build time, Spring practically reduces the scope that the JVM needs to warm up at start. Leyden, with its AOT cache, no longer operates on a chaotic clump of classes, but on a predictable, slimmed-down graph that Spring has already cleaned and materialized.

No wonder early experiments show synergy: even before Leyden, Spring AOT optimizations alone gave about a 15% startup boost on the classic JVM, and “pre-main” improvements from Leyden can boost this effect even further. In practice, this means that Java - the same Java we got used to calling “heavy” - is starting to behave more and more like an ecosystem with built-in, hybrid AOT: part of the work is done by the framework, part by the JVM. The container rises faster, eats less RAM, and depends less on dynamic generation happening at startup. Native builds have less matter to analyze, and AOT gets small, well-described blocks to work with instead of one mega-jar.

Interestingly, we can add to this Spring Data 2025.1 with repositories prepared Ahead-of-Time. Methods like findByEmailAndStatus stop being mysterious spells interpreted at application startup and become regular, generated code, compiled along with the rest of the system. Startup is faster, fewer things happen “in the background,” and behavior in native images stops being a lottery.

A Tale of Two AI Streams

However, a no less interesting part of this puzzle concerns AI. Spring AI is clearly diverging into two development lines.

The 1.1 branch closes the Spring Boot 3.5 era: it’s a “broadening” release, not a table-flipper. In practice, this means you can already build sensible agentic workflows in the 3.5 ecosystem: you pick up the Spring AI starter, configure a provider, define a few tools, and the rest – from the MCP skeleton, through JSON mapping, to integration with ChatClient – is delivered by the framework. Spring AI 1.1 is “AI for today’s projects” – maximally compatible with existing Boot, focused on stability, use-case coverage, and integration with what you already have in your monoliths and microservices.

Simultaneously, ream is currently working on the 2.x line deliberately breaks this compromise and is designed in tandem with Spring Boot 4. Here, the theme is redesign, not just expansion: full compatibility with Boot 4, a new API shape, separation of reactive and imperative ChatClient, preparation for JSpecify and null-safe contracts (which Spring officially announces as a goal for 2.0), and better embedding of MCP and AOT in the very heart of the architecture. For the developer, the difference comes down to direction: 1.1 is the fast track to add AI to an existing 3.5 architecture, but 2.x is a conscious decision that you are building a system where LLMs, MCP agents, and classic Spring services create one, coherent, first-class stack.

@Service

public class BookingAgent {

private final ChatClient chatClient;

public BookingAgent(ChatClient.Builder builder) {

this.chatClient = builder

.defaultSystem(”You are a booking assistant.”)

.defaultTools(”bookingTools”) // References a bean, not just a function

.build();

}

// Defined once, used by Agents and LLMs “automagically”

@Tool(description = “Check room availability for a given date range”)

public boolean checkAvailability(@NonNull LocalDate from, @NonNull LocalDate to) {

return bookingService.hasSlots(from, to);

}

}And I suspect the difference in capabilities will only widen - if only to motivate people to migrate to new versions 😉.

To sum it up - it’s very clear that Spring has drawn two parallel realities.

Spring 6 + Boot 3 is now the stable set – stable, known, ideal for systems entering the maintenance phase that just need to work, not chase every novelty.

On the other side, we have the new baseline: Spring Frameworks 7, Spring Boot 4, fresh Spring Data, and Spring AI 2.x. This is where Jakarta EE 11, JSpecify, AOT, vector search, MCP agents, and lightweight runtimes for AI originating from Spring Boot 4.0 await.

Honestly? The scope of changes is large enough that I expect a lot of serious projects on Spring 6 will simply stay there – at least for a few years. It will be a very comfortable haven: support is there, everything is familiar, business is happy. But that’s exactly why the question is no longer “is it worth upgrading.” The real question is: in which world do you want your system to live in five years - in the safe, tamed 6/3, or on the new, wilder, but also much more promising 7/4 terrain?

I have my suspicions where the most ambitious teams will end up - or those who want to migrate gradually, without a major Big Bang when support ends... but we’ll see.

PS: There was no edition last week as I was recently traveling, with opportunity to make up some bucket list TV Shows on plane. And as a pre-Disney Star Wars fan... OMFG.

PS2: Next week I’ll be speaking at #KotlinDevDay in Amsterdam! See you there 😊