Everything you might have missed in Java in 2025 - JVM Weekly vol. 158

As they say - new year, new us. But before we jump full-speed into 2026, it’s time to clear our heads and go through a (slightly overdue) recap of 2025

And the truth is - like year ago - I thought it would be a bit shorter... but quite a lot happened.

It took a bit since last JVM Weekly issue, so I had a lot of time… and may have overdone it a bit as original draft had 43 pages (and that’s before all the memes 😥). Not to worry, it was cut down, but still you should expect a monstrum of edition.

Sooo… without further ado - let’s start!

1. Language and Platform

We’ll start our “small” overview with JVM languages and all the changes happening within the JVM itself. I’ve selected only the most important new developments… although even those are plentiful. The order is random (more along the lines of “whatever came to mind first,” so there’s a certain chaotic prioritization to it). Enjoy!

Java turns 30!

Let’s start with the birthday wishes: Java this year turned 30 and has entered its fourth decade with style, under Oracle’s banner. Already back in March, JavaOne 2025 adopted an anniversary theme, adding retrospective keynotes and a special “Java at 30” track. The Inside Java newsletter also covered the behind-the-scenes details and celebration plans in its May issue, encouraging the community to join in. On top of that, May 22nd saw a six-hour livestream featuring James Gosling , Brian Goetz , Mark Reinhold , and Georges Saab , hosted by Ana-Maria Mihalceanu , Billy Korando , and Nicolai Parlog.

Partners and vendors joined the toast: JetBrains launched the #Java30 campaign with a What’s your inner Duke? quiz and limited-edition T-shirts up for grabs.

JetBrains also published a “Java Good Reads” list, released a plugin that changes the IDE splash screen, and even dropped a “Java 30” TikTok duet track. And before anyone tries to be cool asking, “What even is TikTok?”, just go play that song.

But that’s not all! Here are a few more highlights:

Azul hosted its virtual event, Duke Turns 30, as early as March, gathering Java Champions for panels on the future of JVM performance.

Also in March (because who says you have to celebrate only on your actual birthday?), Payara looked back at Java’s journey, highlighting the evolution from set-top boxes to microservices in the cloud.

The community joined in too: Cyprus JUG hosted an evening of lightning talks and a Duke cake on May 23rd, and similar events popped up in the calendars of many JUGs and conferences, adding special anniversary sessions.

The upshot of all these distributed but coordinated initiatives is more than just a nostalgic tribute: joint events, open-access content, and new IDE plugins are strengthening the network of relationships that has kept the Java ecosystem vibrant for 30 years - and is preparing it for another decade of innovation.

And hey, in just ten years we’ll be celebrating Java’s 40th. Because, let’s face it, Java is forever.

Virtual Threads finally without Pinning

For nearly two years since their debut in JDK 21 (yes, JDK 21 was published 2 years ago), the results of Project Loom had one major “but” that effectively cooled enthusiasm in large codebases: pinning virtual threads on synchronized monitors. In theory, virtual threads were meant to be a lightweight and massively scalable at the same time, but in practice every synchronized block could pin them to a platform thread - destroying scalability where Java has the most legacy code… so in places where failures tend to surface at the least expected moment. Yes, the documentation warned about it, conference talks advised migrating to ReentrantLock, but in reality teams looked at millions of lines of existing Java and postponed Loom “until later.” I personally had that discussion more than once.

JDK 24 closes this chapter. Thanks to changes in the JVM monitor implementation (JEP 491), virtual threads are no longer automatically pinned when entering a synchronized block. As long as they do not perform operations that genuinely require binding to an OS thread, synchronized blocks can be unmounted and remounted just like any other virtual thread.

The importance of this change is hard to overstate, because - contrary to what might seem to a generation raised on java.util.concurrent, those summer children - synchronized is not an exotic detail but a core Java idiom that has been present from the very beginning in standard libraries, frameworks, application servers, and business code that has been running in production for decades… and will likely remain there for decades to come (Lindy effect, anyone?). Previously, Loom required teams to undertake conscious, often costly refactoring to avoid pinning. Now virtual threads become compatible with idiomatic Java of the past, so migration stops being an architectural project and becomes a purely runtime decision.

It is the moment when the narrative around Loom can finally change. Until JDK 24, it was irresponsible to approach the topic in any way other than “virtual threads are great, but…”, and as we all know, the “but” negates everything that comes before it.

Visualization:

Stream Gatherers finally open up the Stream API

From the very beginning, the Stream API contained a certain contradiction. On the one hand, it offered an elegant, functional way to describe data processing - it is probably the widest used “new” Java feature. However, it was surprisingly closed to extension, which clashes strongly with what one would expect from this kind of functionality… especially people coming from more functional background were rolling eyes. For years, JVM developers kept coming back to the same problem: as long as map, filter, and reduce are enough, everything is fine. But as soon as you need windowing, stateful scanning, rolling aggregates, or more complex transformations, all that elegance disappears into the depths of collect() and custom, hard-to-read Collectors.

JEP 485 and Stream Gatherers are a direct response to this long-standing tension. Instead of stuffing all the logic into a terminal collector, you can now define your own intermediate operations that behave like native elements of the pipeline. windowFixed, scan, fold, and other stream-processing patterns stop being hacks and, crucially, they preserve lazy evaluation and compose naturally with the rest of the stream. In practice, this means less imperative code, fewer external libraries, and much better readability in places where streams previously lost out to classic loops (which are surprisingly flexible pattern in the end).

Also, it’s good to see Java is increasingly choosing the path of “opening up existing abstractions” rather than creating entirely new APIs from scratch.

Class-File API and the end of the “ASM Dependency Era”

If Stream Gatherers change the day-to-day style of writing code - and I suspect most of you will use them at some point, even indirectly through a third-party library - then Class-File API (JEP 484), while remaining largely invisible, changes the very foundations on which the JVM ecosystem has stood for years. For two decades, bytecode manipulation was in practice synonymous with a single library: ASM. Every framework that generated or modified classes - Spring, Hibernate, Mockito, Byte Buddy, testing tools, profilers - had to rely on an external project that was constantly racing ahead of Java’s evolution. Even Java itself used it internally.

This was a quiet but very real structural problem. Every new JDK release meant a race: does ASM already support the new classfile format? Have the frameworks caught up? Will a preview feature break builds? The ecosystem lived in a state of permanent synchronization with a library that was formally “external” but, in practice, absolutely critical.

JEP 484 puts an end to this arrangement. Manipulating .class files becomes part of the JDK, with an official API and compatibility guarantees for future versions of the format. Responsibility for the evolution of the classfile returns to where it always should have been: the platform itself. Frameworks no longer have to guess how to read a new version of bytecode and can instead rely on a contract provided directly by Java.

Even though most of you will never touch classfiles directly, this is a change with enormous significance for the long-term maintainability of the platform. Fewer dependencies, fewer risky upgrades, less “waiting for someone to release a new version of ASM.” But it’s also something more: the internalization of critical infrastructure as certain parts of the ecosystem are too fundamental to live outside the standard library.

Class-File API won’t suddenly make the average developer start writing bytecode-level code (thanks God). But for framework authors, tool builders, and platform engineers, it’s one of the most important JEPs in years - one that reduces friction across the entire ecosystem.

Java enters the Post-Quantum Era before it becomes necessary

Post-quantum cryptography is a topic that’s easy to dismiss with a shrug: “quantum computers aren’t breaking RSA yet, so we still have time.” JEP 496 and JEP 497 introduce the first native implementations of the ML-KEM and ML-DSA algorithms into Java—used for key exchange and digital signatures respectively - aligned with the newly finalized NIST FIPS 203 and 204 standards.

Behind this lies the very pragmatic “harvest now, decrypt later” concept. Data encrypted today with classical asymmetric algorithms can be intercepted and decrypted in the future, once quantum hardware matures. For sectors such as public administration, banking, defense, healthcare, or data archives, the implication is straightforward: if information needs to remain confidential for 20–30 years, migration has to start now - not on the day the first “breakthrough” quantum computer appear

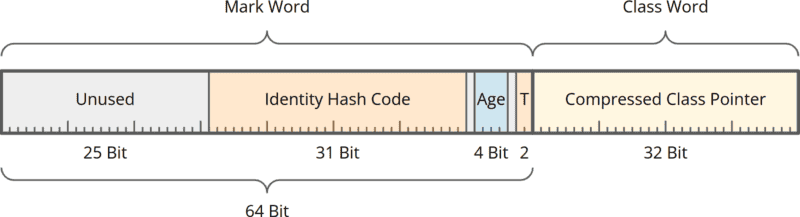

Compact Object Headers Graduate from Experimental Status

This is one of those JVM changes that doesn’t alter a single line of code, yet can completely change the economics of an application. JEP 519 moves Compact Object Headers from the experimental phase into full production, closing out years of work on slimming down one of the most fundamental structures in Java: the object header.

For decades, the object header in HotSpot was relatively “fat” - 96 or even 128 bits, depending on configuration and architecture. It carried everything: synchronization data, GC information, the class pointer, the hash code. JEP 519 reduces this overhead to 64 bits without sacrificing functionality. The result? In applications with a large number of small objects - which in practice means almost every modern JVM service - heap usage drops by an average of ~22%. And that’s no small thing. In the world of microservices, containers, and cloud-native deployments, memory is one of the primary operational costs. A smaller heap also means smaller pods, smaller VMs, faster cold starts, shorter GC pauses, and very real reductions in infrastructure bills.

Compact Headers have been tested, measured, and benchmarked extensively on real workloads. Promoting them to stable version means that OpenJDK considers them safe not only from a performance perspective, but also expects no surprises in synchronization, hash codes, or interactions with the garbage collector.

Pinky swear.

Scoped Values — the Quiet Successor to ThreadLocal

Scoped Values are one of those Project Loom features that don’t make much noise (at least not as much as Stream Gatherers), yet they significantly change how safe, concurrent code is written in Java.

The problem Scoped Values address is old and well known: ThreadLocal. For years, it was the only reasonable way to propagate context - request IDs, security context, transactions, locale - without threading it through every method parameter. But ThreadLocal has two fundamental flaws. First, it lives as long as the thread does, which in a world of thread pools led to leaks, subtle bugs, and “bleeding” context. Second, it doesn’t fit virtual threads, where a thread stops being a long-lived carrier of context and becomes a lightweight, ephemeral abstraction.

Scoped Values invert this model. Instead of binding data to a thread, they bind it to an execution scope. A value is visible only within a clearly defined block, automatically propagates down the call stack, and—crucially—disappears exactly when the scope ends. No cleanup, no leak risk, no magical hooks. Another advantage of Scoped Values is that they are easier for the JVM to optimize. Their immutable nature and bounded lifetime mean the runtime knows precisely when a value exists and when it is no longer needed.

In short: if ThreadLocal was a hack that allowed Java to survive the era of application servers, Scoped Values are the mechanism that lets it enter the Loom era without repeating the same mistakes.

But remember - there is nothing wrong in a good hack. Even Gods-and-Saviours are doing that from time to time

JFR enters everyday observability

Java Flight Recorder has long been one of the most underrated components of the JVM. Powerful and low-overhead, yet often treated like a “black box” that you only look into after something goes wrong. JDK 25 clearly changes this role. The expansion of JFR in 2025 shows that Oracle increasingly sees it as a continuous source of data about application behavior, not just a post-mortem tool.

A key step here is JEP 509, which introduces CPU-time profiling on Linux. Until now, most profiles were based on wall-clock sampling, which in shared environments—containers, cgroups, noisy neighbors—often led to misleading conclusions. CPU-time profiling answers a much more practical question: where does the processor actually spend its time? This is especially important in the cloud, where every millisecond of CPU has a real cost at scale, and the difference between “waiting” and “computing” is crucial for optimization.

The second element, JEP 520, moves JFR toward analyses that previously required external tools or costly instrumentation. Method Timing & Tracing with bytecode instrumentation makes it possible to measure method execution time with much greater precision, without manually attaching profilers or agents (the JVM ones—for AI agents, we’ll get to that later). For the first time, JFR starts looking inside application code, not just observing it from the runtime level.

All of this is tied together by cooperative sampling - a mechanism that improves measurement accuracy while maintaining very low overhead. Instead of aggressively interrupting threads, the JVM cooperates with the executing code, resulting in more stable and representative data. In practice, this means JFR can run continuously in production without fear of a noticeable performance impact. Java Flight Recorder therefore stops being a Plan B for when the world is already on fire, and starts becoming the default way of understanding a JVM application in motion.

From backstage: this is the moment Substack informed I’m approaching the email limit - What can I say, are you f*cking kiddin’ me? I’m just getting up to speed.

Project Valhalla - After a decade, Java finally touches the metal

Project Valhalla is probably the most patiently developed project in the history of OpenJDK. When Brian Goetz announced it back in 2014, the Java world looked very different: there was no Loom, GraalVM was still an academic experiment, and “cloud-native” hadn’t yet become an overused buzzword. For many years, Valhalla existed more as an idea than a roadmap—names changed (inline types, value types, primitive classes), and assumptions were alternately tightened and relaxed.

In 2025, that changed. JEP 401: Value Classes and Objects reached Candidate status, and Oracle released the first early-access builds. This is the first moment when Valhalla stopped being just a Brian Goetz slide deck and became a concrete proposal for changes to the language and the VM.

What’s most striking is how little changes on the surface. One new keyword - value - placed before class or record… and that’s basically it. But beneath this modest syntax lies a fundamental shift in Java’s object model. Value classes give up object identity. Two objects with the same field values are indistinguishable - == ceases to be a reference comparison and becomes a value comparison. It’s a radical but consistent decision: if something has no identity, the JVM no longer has to pretend that every instance “lives its own life” on the heap.

Brian Goetz has summed up Valhalla in a single sentence for years: “code like a class, work like an int.” The core promise of Valhalla is flattening—the ability to place value object data inline in memory, without an extra layer of indirection. An ArrayList<Point> where Point is a value class is no longer an array of pointers to objects scattered across the heap, but a compact array of coordinates. Fewer dereferences, fewer cache misses, better data locality. This is exactly the kind of optimization that’s obvious in C or C++, but was historically out of reach in Java.

Why does this matter so much right now? Goetz often points out that the JVM memory model dates back to the early 1990s. In that world, the cost of memory access and the cost of arithmetic were comparable. In 2025, the difference is on the order of 200–1000×. Java, with its pointer-centric object model, pays a real price for this—especially in numerical code, game engines, stream processing, ML, and HPC. Valhalla is an attempt to regain control over memory layout without abandoning the safety and abstractions that made Java popular in the first place.

Importantly, Valhalla’s design in 2025 is far more pragmatic than in its early iterations. Earlier proposals assumed almost “sterile” isolation of value types. JEP 401 - still not yet targeted to a specific JDK release - allows abstract value classes and softens the boundaries between the reference world and the value world. This signals that the project aims not for academic purity, but for real-world adoptability, including in existing codebases.

At the same time, after years of “not yet,” we finally have a concrete JEP, concrete early-access builds, and a very clear trajectory. Java is beginning to repay its debt to the hardware it actually runs on - and has a chance to change the deepest foundation of all: the relationship between objects and memory.

Congratulation Valhalla team! However I have one thing in my mind

Project Panama and Project Babylon - Java steps beyond its own walled garden

If Loom changed the way Java thinks about concurrency, and Valhalla about memory, then Panama and Babylon go one step further and evolve how the JVM cooperates with the world beyond itself. For decades, Java has been a safe, portable, and… hermetic platform. Integration with native code existed, but JNI was a tool from the “use only as a last resort” category. GPUs, SIMD, specialized hardware? That usually meant C++ wrappers with a thin layer of Java on top. Panama and Babylon are an attempt to break away from this model - without abandoning the JVM.

Project Panama, whose culmination was the introduction of the stable Foreign Function & Memory API, tackles the most down-to-earth and painful problem: how to talk to native code safely and efficiently.

But that’s only half the story. Panama solves how to get outside JVM, but not why Java kept losing in areas such as HPC, GPUs, or intensive numerical computation. And that’s where Project Babylon comes in.

Babylon is one of the most ambitious projects in OpenJDK - and at the same time one of the least understood. Its goal is not to “speed up Java,” but to make Java a language capable of mapping itself onto modern hardware. In practice, this means enabling Java code - when properly described - to be compiled to different backends: CPUs with SIMD, GPUs, and AI accelerators. Not through magical runtimes, but through an explicit, analyzable computation model.

The key here is its connection to Valhalla and Panama. Valhalla’s value classes make it possible to describe data structures, while Panama provides safe access to memory and native ABIs. Babylon ties this all together by delivering a model in which the JVM can understand the semantics of computations, not just execute them on a CPU. Projects like TornadoVM already show today (which we’ll get to shortly) that Java can be a viable language for GPU programming - Babylon is meant to ensure this stops being a curiosity and becomes a feature available to the “common programmer.”

And that’s important - as Java is no longer just a language for backends and microservices. It is starting to become an infrastructural language that can handle everything: from classic services, through AI inference, to heterogeneous computing. And importantly - without copying the C++ or CUDA model. While preserving type safety, garbage collection, and the tooling that have been its advantages for years.

For now, Babylon is still a research project, but by the end of 2025 it remains one of the missing pieces of a puzzle that has been taking shape in OpenJDK for over a decade. If you want to learn more - this is the best material you can find nowadays.

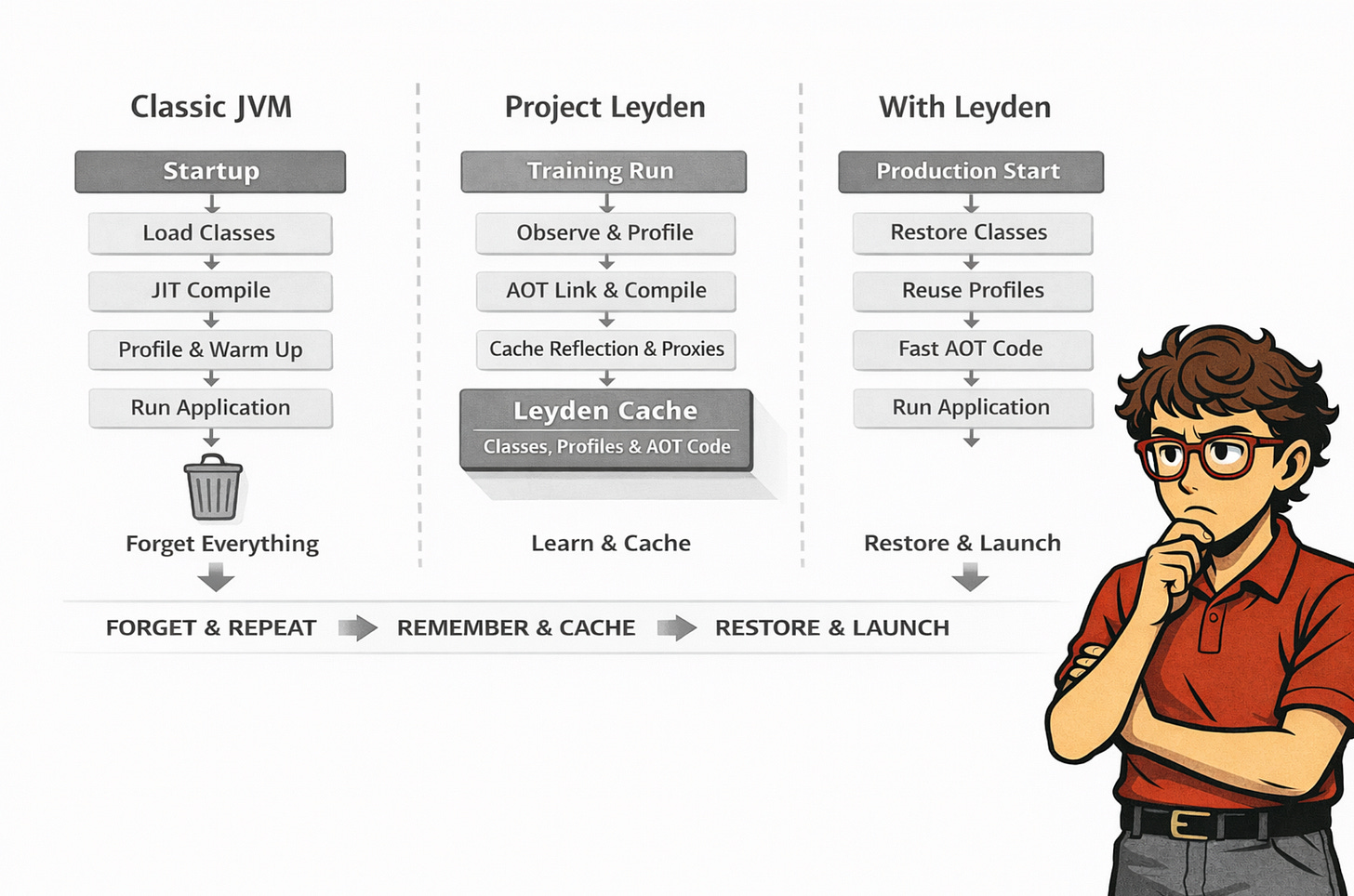

Project Leyden: AOT as an Answer to GraalVM Native Image

For years, the discussion around JVM application startup time has been dominated by a single solution: GraalVM Native Image. Radically effective and impressive in benchmarks, but paid for with real costs - long compilation times, a “closed world,” and constant battles with reflection and libraries that assume JVM’s dynamic nature. Project Leyden was created as a conscious alternative to that philosophy. Not as yet another AOT mode, but as an attempt to achieve similar benefits without giving up what has defined Java for decades.

The key assumption behind Leyden is that most server applications are not chaotic. On the contrary - they are surprisingly predictable, boring even. The same classes are loaded on every startup. The same code paths warm up at the beginning. The same proxies, the same reflection metadata, the same execution profiles. JVM has long been able to see these patterns, but until now it discarded this knowledge on every restart - Leyden changes exactly that.

Leyden’s philosophy is speculative runtime optimization. The JVM observes the application during a so-called training run and assumes that future runs will be similar. Execution profiles are not random; they are a stable artifact of the application: classes that were needed will be needed again, and methods that were hot are worth preparing in advance. Instead of starting “from scratch” on every launch, the JVM begins to learn its own behavior.

In 2025, Leyden began to materialize in the mainline JDK. The foundation consists of three JEPs that together define a new JVM startup model. JEP 483, introduced in JDK 24, enables Ahead-of-Time Class Loading & Linking - the most expensive part of JVM startup can be done in advance and stored in a cache. JEP 514 simplifies the launch ergonomics, reducing the entire workflow to a single, sensible command instead of a set of experimental flags. JEP 515 allows method execution profiles to be preserved across runs, opening the door to much more aggressive optimizations without sacrificing safety.

In August 2025, Leyden Early Access 2 appeared, showing where the project is actually heading. For the first time, we saw the outline of AOT code compilation - methods can be compiled to native code during the training run and stored in a cache, so the work doesn’t have to be repeated on the next startup. On top of that comes AOT for dynamic proxies and reflection data - two areas that historically caused the biggest problems for both the classic JVM and Native Image. Crucially, all of this still works within HotSpot, without closing the world and without breaking the contract of dynamic behavior.

Leyden is not trying to beat GraalVM Native Image on its own turf. Instead, it redefines the reference point. If Native Image is an extreme - minimal startup at the cost of flexibility - then Leyden pushes the classic JVM as far toward “fast startup” as possible without abandoning dynamism. For the vast majority of enterprise applications, this is exactly the compromise that was missing. Project Leyden is, in practice, OpenJDK’s answer to the question: can the JVM be fast at startup without ceasing to be a JVM? In 2025, for the first time, the answer began to sound like: yes.

And since we’ve already invoked GraalVM…

GraalVM in 2025 - From “Java’s Savior” to a specialized runtime (with AI Inside)

Well… 2025 was one of the most turbulent years in GraalVM’s history. Not technologically - because on that front GraalVM made enormous progress - but strategically. Oracle very clearly shifted its priorities, effectively closing a certain era in thinking about GraalVM as “the future of Java.”

The most important signal came early: GraalVM for JDK 24 is the last release licensed as part of Java SE. The experimental Graal JIT, which in Oracle JDK 23 and 24 could replace C2 as an alternative compiler, has been withdrawn. Native Image is no longer part of the Java SE offering, and Oracle is explicitly steering customers toward Project Leyden as the default path for JVM startup and runtime optimization. For many observers, this was a “wake-up moment”: GraalVM is not disappearing, but it is no longer the universal answer to all of Java’s problems that it seemed to be over the past decade.

At the same time - and here lies the most interesting paradox - GraalVM has never been technologically stronger than it was in 2025. Instead of focusing on being a “better HotSpot,” the project fully embraced its unique identity: extremely aggressive AOT, a compiler as a research platform, and a proving ground for techniques that the classic JVM cannot adopt as quickly.

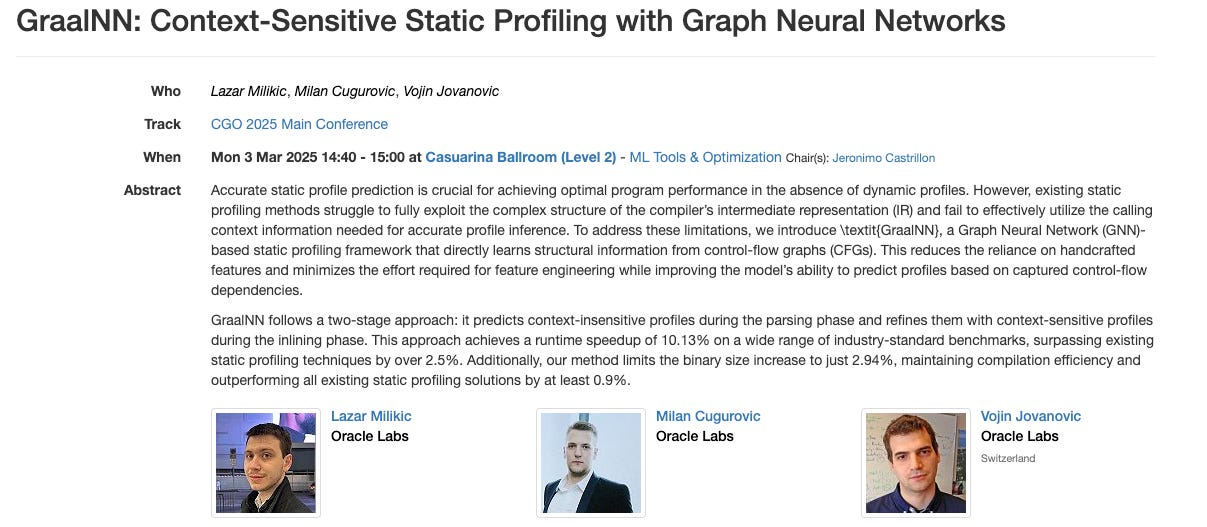

The best example of this shift is GraalNN - a neural-network-based static profiler. It is one of the most underrated yet most radical ideas in the compiler world in recent years, and it fits perfectly into the zeitgeist of 2025. Instead of relying solely on runtime profiles or simple heuristics, GraalVM uses a trained neural network that predicts branch probabilities based on the structure of the control flow graph - the compiler starts guessing how the code will behave before it ever runs. This is an evolution of the earlier GraalSP based on XGBoost, which has been enabled by default since version 23.0 - but GraalNN goes further. On top of that comes SkipFlow, an experimental optimization that tracks primitive values across the entire program and evaluates conditions already at the static analysis stage. In the world of Native Image, where every kilobyte and every method matters, this is a very concrete advantage.

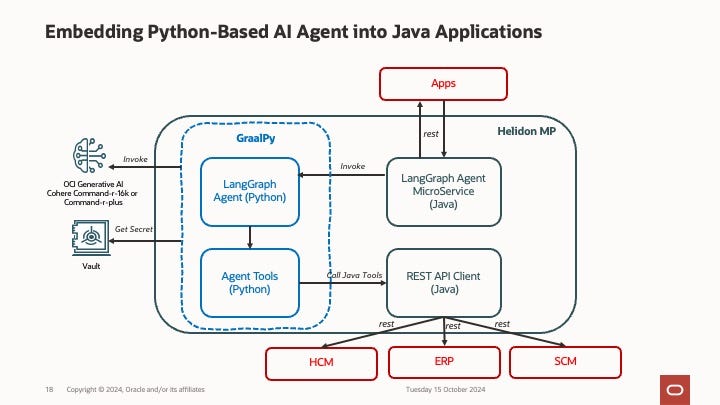

In parallel, a new and interesting thread emerged: GraalVM and AI at the application level. Quarkus began exploring streamable HTTP and MCP in the context of LLMs, based on its fork of the project - Mandrel - while Oracle is positioning GraalPy as a runtime for building AI agents and workflows (e.g., LangGraph) with very low overhead and good integration with JVM-based backends.

At the same time, support for macOS x64 was dropped without sentimentality - GraalVM 25.0.1 is the last release for Intel; the future is exclusively Apple Silicon.

And this brings us to the key conclusion the community reached in 2025. GraalVM is no longer seen as a competitor to HotSpot and Leyden (rather, Leyden stopped being “GraalVM for the masses,” gradually pushing its older sibling out of its natural habitat). Instead, it has found its place as a specialized runtime and compiler: ideal where extreme trade-offs matter - serverless, CLI tools, edge computing, AI inference, native integration, minimal binaries. As Leyden takes over the mainstream JVM, GraalVM occupies the extreme end of the spectrum.

This was a difficult but healthy narrative correction. For years, GraalVM was the answer to criticisms from the Rust or Go communities, proudly pointing out that Java also had its own native format - though one that never broke into production to the extent the surrounding community had hoped. Now that it no longer has to “save Java,” it can focus on what it does best: experimenting faster than the mainline, bringing ML into compilation, and pushing the boundaries of AOT. And Java - paradoxically - comes out better for it, because instead of one tool for everything, it gains a coherent spectrum of solutions.

I think it’s fair to say that in 2025 it became clear: GraalVM is not the future of the entire JVM. But without GraalVM, that future would look significantly poorer.

Jakarta EE - The Year that breathed life into a “Dead” Platform

If anyone had written Jakarta EE off a year ago, 2025 must have felt like a cold shower. This was the year the platform stopped merely catching up and actually started building its future.

Jakarta EE 11 - after 34 months since the previous release - finally saw the light of day. First came the Core Profile (December 2024), then the Web Profile (March 2025), and the full platform on June 26. The delay, however, made sense: the Working Group spent that time thoroughly modernizing the TCK - migrating from Ant/TestHarness to Maven/JUnit 5/Arquillian. Boring? Yes. But it was precisely this “plumbing” that had blocked progress for years and scared off new vendors.

Version 11 itself brings two stars: Jakarta Data 1.0 - an answer to Spring Data without Spring, with repositories defined via interfaces and implementations generated automatically—and Jakarta Concurrency 3.1 with full support for Virtual Threads. On top of that come Java Records in Persistence and Validation, the removal of the Security Manager, and the deprecation of Managed Beans. The platform is finally speaking the language of modern Java.

And that’s not all. In March, Jakarta NoSQL 1.0 was approved - a specification standardizing access to document, graph, and key-value databases with an API modeled after JPA. It didn’t make it into EE 11, but it paves the way for future profiles.

And in the fall? Jakarta Agentic AI - a project under the Eclipse Foundation umbrella (initiated by Payara and Reza Rahman) that aims to define a vendor-neutral API for AI agents: lifecycle, integration with CDI and REST, and standard guardrails. The first release is planned for Q1 2026. At the same time, MicroProfile AI is taking its own, more pragmatic path - trying to integrate LangChain4j into the ecosystem without waiting for full specifications.

Greetings to the rest of technical community from the more peaceful wotld.

However, for those who crave emotions and enjoy the behind-the-scenes drama - over the summer, a governance conflict played out on the mailing lists. For years there have been discussions about merging MicroProfile into Jakarta EE (a logical step, since MicroProfile already depends on the Core Profile), but such a merge requires a so-called super-majority. David Blevins (Tomitribe) publicly announced that a coalition of several vendors has enough votes to block it—not because they oppose integration per se, but pending resolution of a conflict of interest. The crux of the dispute: within the Jakarta EE Working Group structure sits EE4J—a parent project that includes GlassFish. Blevins argues that the WG’s budget, marketing, and community programs effectively promote one implementation at the expense of competitors (Payara, Open Liberty, WildFly, TomEE). His proposal: split EE4J into a separate structure, and let the Jakarta EE WG focus solely on specifications. OmniFish (the GlassFish steward) agrees to the split but denies any intentional favoritism—calling it historical baggage that is gradually being removed. Current status: in November, a proposal passed to retain the org.eclipse.microprofile.* namespace in the event of a merge—a signal that the community is preparing for integration without repeating the pain of javax.* → jakarta.*. but the EE4J issue remains unresolved.

Additionally: the plan for Jakarta EE 12 (scheduled for July 2026) has already been approved - mandatory JDK 21, support for JDK 25, new specifications Jakarta Config and Jakarta Query, deprecation of the Application Client, and further consolidation of the data layer.

Not a bad year for a “dead” platform.

Scala Says Goodbye to JDK 8

For a decade, JDK 8 was the anchor of the JVM ecosystem - but that era is coming to an end. Spring Boot 3 requires JDK 17. Jakarta EE 10 has a minimum of JDK 11. Hibernate 6, Quarkus 3.7, Micronaut 4 - all have gone down the same path. And it is precisely in this context that Scala made its most symbolic move in 2025. In March, the Scala team officially announced its decision: JDK 17 will become the new minimum, starting with Scala 3.8 (currently in RC4, so the release is likely imminent) and the next LTS (most likely Scala 3.9). Not JDK 11 - straight to 17. The discussion about whether to also drop JDK 11 revealed no convincing reason to keep it—11 is now almost as outdated as 8.

The direct reason? The implementation of lazy val in Scala - one of the language’s most distinctive constructs - relies on low-level operations from sun.misc.Unsafe, which are necessary to ensure correct behavior in multithreaded environments (initialization must happen exactly once, even when multiple threads access the value simultaneously). The problem is that Oracle has been planning to remove these methods for years - JEP 471 officially deprecates them, and future JDKs (25+) may remove them entirely. Scala therefore had to rewrite the lazy val implementation using a newer API (VarHandle), which is only available starting with JDK 9. Maintaining two code paths - the old one for JDK 8 and the new one for newer versions - was deemed too costly.

There is also a beautiful irony in all of this: for years, Scala was ahead of Java (pattern matching, sealed types, ADTs). Java eventually caught up with Scala at the language level - and now Scala can finally take advantage of the bytecode that Java created… inspired by Scala. The loop is complete.

Kotlin and the Moment When K2 Stops Being “New”

After Kotlin’s very dynamic development in 2024, with the highlight being version 2.0 in May, 2025 became a year of normalization. Kotlin 2.2 (June) and 2.3 (December) no longer try to convince anyone that K2 is the future - they assume instead that “the future is now,” and focus on what ultimately determines real adoption: performance, ergonomics, and ecosystem completeness.

The most telling signal is therefore tooling-related rather than language-level. K2 mode became the default in IntelliJ IDEA (from 2025.1). This means that code analysis, completion, highlighting, and refactorings in the IDE are powered by exactly the same engine that compiles the code. JetBrains decided that K2 is stable and fast enough to become the foundation of the entire workflow.

Kotlin 2.2 and 2.3 (which we didn’t covered yet in JVM Weekly, but it time will come) represent a maturation phase - rather than a single “killer feature,” we get a series of small but noticeable improvements. Guard conditions in when, context parameters that organize dependencies, non-local break/continue, multi-dollar string interpolation—these are changes that don’t make a splash (you’ve probably already forgotten what was in the previous sentence), but save time every day. API stabilization (HexFormat, Base64, UUID), compatibility with Gradle 9.0, new mechanisms for source registration - Kotlin stops living “alongside” the JVM toolchain and starts being co-designed with it.

At the same time, Kotlin Multiplatform continues to mature - a technology that for years was both the biggest promise and the biggest question mark. Compose Multiplatform for iOS reaches production-ready status in 2025, and not in the sense of “it works in a demo,” but as a fully-fledged UI stack: native scrolling, text selection, drag-and-drop, variable fonts, natural gestures. Add to that Compose Hot Reload, which dramatically shortens the feedback loop. This is the moment when UI stops being the “weak link” of KMP.

In the same context, Swift Export appears - still in preview, but highly symbolic. Kotlin no longer integrates with Swift via Objective-C, and instead starts exporting APIs directly into the Swift world.

The tooling backend is also being cleaned up. kapt uses K2 by default, old flags are being deprecated, and annotation processing finally stops being a “parallel world” alongside the new compiler. Alongside this, Amper continues to evolve—still experimental, but increasingly positioned as an alternative where Gradle is too heavy and tight IDE integration matters more than maximum configurability.

There is, of course, Kotlin LSP - but it is such an interesting phenomenon in its own right that we’ll come back to it later.

Clojure Is… AI-Skeptical

In 2025, Clojure did something that, in the age of “AI everywhere,” feels almost countercultural: instead of trying to win the fireworks race, it focused on steadily closing the gaps in the language’s and tooling’s foundations. The most “official” rhythm of the year came from successive releases in the 1.12.x line. On paper, these were tiny releases, but they’re quintessentially Clojure: semantic fixes, compiler improvements, visibility and safety issues in LazySeq and STM - the kinds of changes that improve the predictability of systems meant to last for years.

And here’s the most interesting part: this “quiet” year for the language itself collided with a very loud statement from Rich Hickey about AI - a statement that, in many ways, explains why Clojure in 2025 looks the way it does. In early January 2026, Hickey published an essay titled “Thanks AI!” (sneaking into this overview at the last possible moment), in which he directly addresses the side effects of generative AI: from flooding the world with “slop,” through degrading search and education, to cutting off the entry path for juniors (the disappearance of entry-level jobs as a “road to experience”). Classic Hickey: evaluating technology through the lens of whether it reduces complexity and improves the quality of social systems, not just technical ones.

Instead of building “the Clojure AI agent framework of the year,” the community pumped energy into tooling and ergonomics. Clojurists Together’s 2025 reports explicitly show where funding and effort went: to people working on clojure-lsp and IDE integration, on clj-kondo, babashka, and SCI, on CIDER - in other words, on things that shorten the feedback loop and improve the quality of everyday work, regardless of whether an LLM is involved in the background.

And this is, paradoxically, one of the most important things about Clojure in 2025: in a world where many ecosystems respond to AI with a marketing reflex, Clojure responds… like Clojure. Quality, semantics, and tools first. The rest can wait.

Groovy 5.0 - A New (Small) Impulse for a Classic JVM Language

Groovy has a long history behind it - from a dynamic, “magical” JVM language that in the mid-2000s was one of the most interesting alternatives to Java, inspired by Ruby (the ultimate “cool kid” language of its time), through a scripting platform used in Gradle, Jenkins, and Grails, to today’s ecosystem where its mainstream adoption has been declining in favor of Kotlin/Java and more strongly typed tools.

Released in the summer of 2025, Groovy 5.0 is the first major revision since Groovy 4 and an attempt to bring more modern language features and tooling quality into a project that for a long time was seen more as a “support tool” than a fully fledged programming language. The release includes a wide range of improvements: broad compatibility with JDK 11–25, hundreds of new or enhanced extension methods for Java’s standard APIs, a reworked REPL console, better interoperability with modern JDK versions, and a number of conveniences for working with collections and iteration. All of this is meant to ensure that Groovy doesn’t fall behind in the era of newer JVM platforms.

One of the most anticipated features of 5.0 is GINQ (Groovy INtegrated Query) - a SQL-style query language built into Groovy that allows collection and data-structure operations to be expressed in a more declarative way. This functionality already existed in earlier 4.x versions, but in 5.0 it is strengthened and treated as a first-class part of the language. GINQ offers capabilities similar to LINQ in .NET, with from, where, orderby, and select clauses, and support for working with different kinds of data sources.

The community’s reception of Groovy 5.0 has been mixed, which is hardly surprising given the language’s position in 2025. Developers still invested in Groovy appreciate the modern improvements - such as better performance for collection operations, fixes to the REPL and interoperability, and the fact that the project continues to evolve beyond 4.x. As some commentators put it, this is “the best version of Groovy so far,” with hundreds of fixes and extensions. On the other hand, discussions and forum posts also point out that the language continues to struggle with limited adoption and tooling support outside its traditional niches, such as CI/CD scripts, Gradle DSLs, or automation tasks.

All in all, Groovy 5.0 is an interesting release: it delivers new language features, stronger JDK compatibility, and improved ergonomics, while at the same time fighting for attention in a JVM landscape dominated by Kotlin, Java, and statically typed tools. Its role in projects like Gradle (where it is gradually being displaced by Kotlin), Grails (which itself is no longer a popularity powerhouse), or Jenkins shows that the language still has its place - but its development in 2025 is more evolutionary than revolutionary.

2. What’s Happening in the Community

OpenRewrite: From a Tool to an Ecosystem

Not long ago, OpenRewrite existed in the collective consciousness as “that tool for migrating Spring Boot.” Useful and effective, but still fairly narrowly pigeonholed. In 2025, that phase definitively ended. OpenRewrite stopped being a product and started functioning like infrastructure - quiet, embedded, often invisible, but absolutely critical to how code in the JVM ecosystem is modernized today.

A symbolic moment was OpenRewrite being built directly into IntelliJ IDEA starting with version 2024.1. From that point on, it was no longer a plugin for enthusiasts, but a first-contact tool. YAML recipes with autocompletion, inline execution of complex transformations, gutter-based migration runs, and debugging scans and Refaster rules turned automated refactoring from a “special operation” into a normal part of everyday IDE work. When JetBrains treats a tool as part of the editor itself, it usually signals that the ecosystem has matured to a new standard.

In parallel, Microsoft’s App Modernization initiatives built around GitHub Copilot do not “write migrations” themselves. Copilot plans steps, explains changes, and closes error loops—but the deterministic code transformation is performed by OpenRewrite itself. AI analyzes the codebase and proposes a migration sequence, OpenRewrite applies semantic transformations, and Copilot iteratively fixes compilation and test failures. Java 8 → 25, Spring Boot 2 → 4, javax → jakarta, JUnit 4 → 6—without a semantic refactoring layer, this entire process would degrade into little more than prompt engineering and hope. Even the most advanced LLM-based tools still require a deterministic refactoring engine underneath to constrain stochastic behavior.

The same pattern appears elsewhere. Azul integrates OpenRewrite via Moderne rather than building its own refactoring system, combining automated code transformations with runtime insights from Azul Intelligence Cloud.

What’s most interesting is how many tools now rely on OpenRewrite without exposing that dependency prominently. Moderne is the obvious example, but the same pattern can be observed in security auditing tools, compliance platforms, mass repository migration systems, and internal “code remediation” platforms built by large organizations. OpenRewrite is increasingly playing the same role for refactoring that LLVM plays for compilers - a shared substrate on which others can build workflows, UIs, and integrations without reimplementing parsers, visitors, or semantic analysis from scratch.

At the same time, the technical scope of OpenRewrite continues to expand beyond Java. It now supports JavaScript, TypeScript, Android, and increasingly complete Scala coverage, with rapid parser updates tracking Java 25, Spring Boot 3.5, and Spring Cloud 2025. The OpenRewrite recipe catalog has surpassed 3,000 entries, evolving from a simple list of migrations into a living knowledge base that captures how large, long-lived systems actually evolve in practice.

Have fun with JavaScript, OpenRewrite.

Private Equity Enters the Game: Azul Acquires Payara

On December 10, 2025, Azul announced the acquisition of Payara—the company behind the enterprise fork of GlassFish and one of the last truly serious players in the Jakarta EE world. On paper, this looks like a classic product acquisition. In practice, it’s a much deeper move that closes a long sequence of events.

Just a few weeks earlier, Thoma Bravo entered Azul. And when private equity of that scale shows up in a technology company, it’s usually not about maintaining the status quo - it’s about building a platform capable of aggressive growth.

For years, Azul has been a very clearly profiled company: an excellent JDK, extremely strong expertise in performance, stability, and security—but still just one fragment of the overall stack. For large Java customers (you know - the true enterprise+ scale), the story rarely ends at the JVM. It ends with the question: “what about the application server themselves?”

And this is exactly where Payara comes into the picture.

For years, Payara has existed somewhat outside the main hype cycle, consistently serving organizations that could not - or did not want to - abandon Jakarta EE. Banks, public administration, industry - places where applications live for decades, not quarters.

For Azul, this was the missing piece of the puzzle. The acquisition of Payara makes it possible to offer customers a complete, coherent story: from the JDK, through the runtime, all the way to the application platform. One responsibility, one vendor, one operating model. The broader market context is even more interesting. The application server market - declared dead many times over, even in this article itself - is today worth tens of billions of dollars (yes, I was surprised too).

Why? Because microservices and the cloud didn’t erase monoliths - they merely added new layers alongside them. Organizations are migrating, but they do so in stages. And they need platforms that can handle both the “old” and the “new” at the same time.

BM Merges the Red Hat Java Team… and Buys Kafka

Azul isn’t the only company trying to give customers a more focused, end-to-end offering. 2025 brought two IBM moves that, taken separately, look like routine corporate reshuffles—but together form something much more interesting: an attempt to build a coherent enterprise stack that actually lives in real time, instead of pretending to analyze data “almost instantly.”

Early in the year - fairly quietly (unless you read JVM Weekly, in which case not quietly at all) - Red Hat’s Java and middleware teams were merged into IBM’s Data Security, IAM & Runtimes organization. Sounds like just another reorg? Maybe. But the context matters.

Since IBM acquired Red Hat in 2019 for $34 billion, the two companies have effectively been running parallel JVM universes: Red Hat with JBoss EAP, WildFly, and Quarkus and IBM with WebSphere, Open Liberty, and OpenJ9.

Two teams, two roadmaps, two philosophies tackling the same problem. Now they’re meant to be one. The projects remain open source (WildFly and Quarkus were moved under the Commonhaus Foundation), but middleware strategy is now owned by a single organization - not two competing ones.

December, however, brought the real fireworks: IBM buys Confluent for $11 billion in cash. Eleven. Not “considering,” not “exploring” - done, signed, with a premium and full commitment. And suddenly, everything clicks.

Kafka may be the backbone of real-time data, but Confluent has never been profitable - billions in losses over the years - which made many analysts skeptical. IBM sees it differently: 45% of the Fortune 500 already use Confluent products. For a startup (okay, not that small anymore), that’s success. For Big Blue, it’s a list of customers who don’t yet realize they need event-driven architecture bundled with 24/7 support and long-term enterprise contracts.

And this is where Java comes back into the picture. Red Hat gave IBM the platform (OpenShift). HashiCorp (deal finalized this year as well) delivered infrastructure as code. Confluent brings real time.

The newly unified Java/middleware team is supposed to glue all of this into a single, predictable stack for enterprises that want to build event-reactive systems.

It’s an interesting bet: IBM is wagering that the future of enterprise isn’t better dashboards, but architectures where data stops being “what happened” and becomes “what is happening.” And to do that properly, you need runtimes (the Java stack), a platform (OpenShift), orchestration (Terraform), and a circulatory system (Kafka).

Will it work? Time will tell. But one thing is certain: IBM didn’t buy Confluent to improve the next quarterly report. The effects should become visible pretty soon.

Cause always remember the crucial difference:

Canonical Releases Its Own JDK

And while we’re on the topic of JDK teams tied to Linux distributions…

July also brought something unexpected: Canonical announced its own Canonical builds of OpenJDK - binary OpenJDK builds optimized specifically for Ubuntu, including ultra-slim Chiseled OpenJRE containers aimed at cloud and CI/CD environments. This is another step in a growing trend where the JDK is treated as an artifact tightly coupled to the platform, tooling, and ecosystem around it.

Canonical emphasizes that these builds are significantly smaller - up to 50% smaller than popular distributions like Temurin - without sacrificing throughput or performance.

For JVM developers, this means that the choice of runtime environment is becoming increasingly dependent on deployment context: Ubuntu Pro on servers, IBM Semeru or Red Hat OpenJDK/Quarkus in enterprise setups, Microsoft Build of OpenJDK for Azure, and so on.

As a result, choosing a JDK is no longer simply “just OpenJDK.” It’s becoming more complex, with each provider adding its own twist. Canonical focuses on container size reduction and long-term support; IBM and Red Hat emphasize long-term stability and enterprise application compatibility; Microsoft offers builds tailored specifically for Azure.

What’s interesting is how different organizations now view Java - as a set of composable artifacts fitted to their own ecosystems, rather than as “one universal distribution everyone just downloads and uses.” And that’s the broader trend worth paying attention to.

Hibernate ORM changes its license: The end of the LGPL Era

Hibernate’s license change from LGPL to the Apache License 2.0 also has an interesting broader context. For years, LGPL was “safe enough” for Hibernate. It allowed use in commercial projects, didn’t force companies to open their own code, and in practice rarely caused real problems for engineering teams. The issue is that open source reality doesn’t stop at engineers. In many organizations, the mere presence of LGPL in the dependency tree was enough to trigger a red flag—regardless of how liberal its interpretation actually was. For legal departments, intent mattered less than the license header.

This tension grew as the entire ecosystem evolved. Hibernate давно stopped being a “standalone project” and became a foundation of the modern Java stack: Jakarta EE, Quarkus, and newer initiatives centered around the Commonhaus Foundation. These ecosystems share one common trait: a strong preference for the Apache License as the default standard. LGPL increasingly became an exception - something that had to be explained, justified, and pushed through yet another committee.

In that sense, relicensing was a rational move. The question wasn’t whether LGPL is “bad,” but whether it was still compatible with the direction Java as a platform has taken. Apache License provides simple answers to hard questions: you can use it, distribute it, build products on top of it - without nuances, exceptions, or interpretations - and nobody asks uncomfortable follow-up questions. For projects targeting enterprise adoption - and Hibernate very much is one - that simplicity has real value.

So why go all the way? Because the alternative was slow marginalization. Staying on LGPL would increasingly turn Hibernate into “that problematic component” that blocks adoption, complicates audits, and requires extra explanations.

The license change came with real costs and real losses. It required reaching out to hundreds of contributors across 25 years of project history. It was a test of how “alive” an open-source project really is - one that many people treat as a given part of the landscape. Where consent couldn’t be obtained, code had to be removed or split out. Envers remained under LGPL; other modules simply ceased to exist. Trade-offs were inevitable.

Deno vs Oracle: Who Owns “JavaScript”?

JavaScript is the air of the internet today. A language you don’t really choose—it’s just there. In the browser, on the server, in tools, frameworks, builds, and deploys. And precisely because of that, it can be surprising that, formally, the name “JavaScript” is still a trademark owned by one specific company: Oracle. For years, this was one of those legal oddities everyone knew about, but no one had the time or energy to do anything about. Until the end of 2024.

In November, Ryan Dahl the creator of Node.js and Deno - filed a formal petition with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office to cancel the “JavaScript” trademark. The starting point is simple: Oracle inherited the mark from Sun Microsystems in 2009, but since then it has not participated in the development of the language, does not take part in TC39, does not sell products based on JavaScript, and in practice has no real connection to it beyond a historical entry in a registry.

The dispute drags on through 2025, with Oracle consistently refusing to voluntarily relinquish the trademark, rejecting the allegations, and attempting to neutralize the heaviest charge - fraud in the renewal of the mark in 2019, when a screenshot of the Node.js website was presented as proof of use. In legal terms, that turns out to be insufficient to prove intentional deception. The rest of the case, however, remains alive, and in September the parties enter the discovery phase - the most expensive and most brutal part of the proceedings.

In the background, something far more interesting is happening than the lawyers’ battle itself. A community that for three decades has treated JavaScript as a common good suddenly realizes that its name does not formally belong to it. An open letter published on javascript.tm gathers tens of thousands of signatures, including that of Brendan Eich - the creator of the language - as well as people who actually shape its evolution today. Deno launches a fundraiser to cover legal costs, because discovery is not paid for with ideals, but with very real money.

I’m writing about this because, in truth, this is not really a dispute about JavaScript itself, but about whether the trademark system should allow the “hoarding” of names that have become technological standards, or whether it should be able to release them once they stop being anyone’s product. Regardless of how the case ends - and we’ll likely wait until 2027 for a verdict - one thing has already happened: someone finally asked out loud whether JavaScript is still someone’s brand, or simply a language that belongs to everyone.

And sometimes, just asking that question is enough to shake the foundations.

Wish you luck, Deno. You will need it.

JetBrains Reveals Plans for a New Programming Language

In July 2025, Kirill Skrygan, CEO of JetBrains, said in an interview with InfoWorld that JetBrains is indeed working on a new programming language. And no - it’s not Kotlin 3.0, nor another iteration of a familiar paradigm. It’s an attempt to jump an entire level of abstraction.

Skrygan described it in a way that almost sounds old-fashioned: through the history of language evolution. First assembly, then C and C++, then Java and C#. Each step moved the programmer further away from the machine and closer to a mental model. The problem is that we’ve been stuck at this level for years. Today’s developers still translate their intent into classes, interfaces, annotations, and frameworks—even though the real design of a system lives elsewhere: in people’s heads, in architecture discussions, in design docs, diagrams, and domain descriptions.

That gap is exactly what JetBrains wants to address. The new language is not meant to be a “better Kotlin,” but an attempt to formalize what has so far been informal: the system’s ontology, the relationships between entities, architectural assumptions, and decisions that today get lost in comments, Confluence pages, or Slack threads - and later have to be manually reconstructed in code. In other words, everything agents need to operate: context.

The most controversial part of this vision appears when Skrygan talks about natural language. The foundation of the new language is supposed to be… English. But not in the sense of “write a sentence and magic happens.” Rather, as a controlled, semantic representation of intent - something between a design document and a formal system description language. AI agents, deeply integrated with JetBrains tooling, would take this description and generate implementations for different platforms: backend, frontend, mobile - everything consistent, everything derived from a single source of truth.

This distinction matters, because Skrygan explicitly distances himself from the popular slogan that “English will be the new programming language.” His view is surprisingly sober: you can’t build industrial systems in plain English. And that tension is key to understanding the whole initiative. JetBrains isn’t trying to replace programming with prompts. It’s trying to build a formal language of intent - one that looks like English but behaves like a programming language. A kind of spec-driven engineering baked directly into the core of the language.

The organizational context also matters. JetBrains is a private company. It doesn’t need to deliver quarterly narratives for the stock market, and it doesn’t have to chase hype. Skrygan says it openly: people are tired of grand AI declarations. And precisely because of that, JetBrains can afford a long-term experiment that may not produce a sellable product for years. It’s the same logic that once allowed them to invest in Kotlin long before anyone knew it would become mainstream.

Importantly, this new language isn’t emerging in a vacuum. JetBrains is already building infrastructure for a world where the IDE is no longer just a code editor. Junie as a coding agent (and yes, we’ll talk more about Junie later), local Mellum models, deep integrations with LLM providers - all of these are pieces of a puzzle in which code stops being the only artifact and becomes just one of many possible “renders of intent.”

We don’t know the timeline. It’s possible that for years we’ll see nothing but prototypes, internal DSLs, and experimental tools - or perhaps nothing at all. But the very decision to think about a new programming language in 2025 (let’s be honest: who even cares about programming languages in 2025?) already says something. JetBrains clearly believes that the next revolution won’t happen in yet another version of Java, Kotlin, or TypeScript, but in a place where we still lack sufficient precision - where code ends and thinking about the system begins.

And since we’re already talking about JetBrains…

The End of the Two - IntelliJ IDEA Era

December 2025 brought a decision that would have seemed unthinkable just a few years ago: the end of the split between IntelliJ IDEA Community Edition and Ultimate. Starting with version 2025.3, there is a single IntelliJ IDEA. Some features are available for free, others require a subscription or a 30-day trial - but the product no longer pretends these are two separate worlds.

For a long time, the Community vs. Ultimate split made sense. Community was a clean IDE for Java and Kotlin; Ultimate was a platform for the enterprise world—Spring, databases, and everything considered “serious.” The problem is that the line between “basic” and “enterprise” has become increasingly blurred. Today, even a student project very quickly touches Spring Boot, SQL, database migrations, or simple web integrations. Keeping these features behind a paywall increasingly stopped being monetization and started becoming frustration - and an onboarding barrier that many simply wouldn’t cross.

At the same time, two products meant two development pipelines, two test suites, two backlogs, and constant decisions about whether a given feature “belongs” in Community or already in Ultimate. In practice, this led to duplicated effort and slowed overall development. Consolidating into a single IDE is, first and foremost, an engineering decision: one codebase, one distribution model, one evolution path. Very Kotlin Multiplatform in spirit.

A (very user-friendly) side effect is the shift in the boundary of free features. Basic support for Spring and Jakarta EE, the Spring Boot wizard, SQL tooling, database connection configuration, and schema browsing suddenly stop being “enterprise-only” features - not because JetBrains became philanthropic, but because without them IntelliJ simply stops being a realistic starting tool for new developers.

But the real reason for this change, in my view, is much more down to earth: pressure from Cursor, Windsurf, Antigravity, and the entire wave of VS Code forks with built-in AI features. When the competition gives you not only a free IDE, but also an intelligent assistant that writes code, refactors, and debugs, the discussion of “should I pay for Spring support?” starts to sound a bit absurd. JetBrains clearly realized that fighting for user base now matters more than optimizing revenue from basic licenses.

Monetization doesn’t disappear - but it shifts dramatically. Instead of selling access to frameworks (especially for quasi-commercial users - companies will buy full IntelliJ anyway), JetBrains will sell AI-assisted development, advanced code analysis, team collaboration, and enterprise tooling. Upselling moves higher up the stack - where real value lies in productivity and scale, not in the mere fact that the IDE “understands Spring.”

This is the end of a certain era (a phrase heavily overused in 2025), but also an open admission of a new reality: if JetBrains wants a chance to compete with free, AI-powered editors, it first has to keep users inside its ecosystem. Limiting basic functionality was only accelerating the exodus to tools like Cursor. From 2025 onward, there is one IntelliJ. And this isn’t a gesture of goodwill, but a necessity in today’s world. That is what industry expects right no

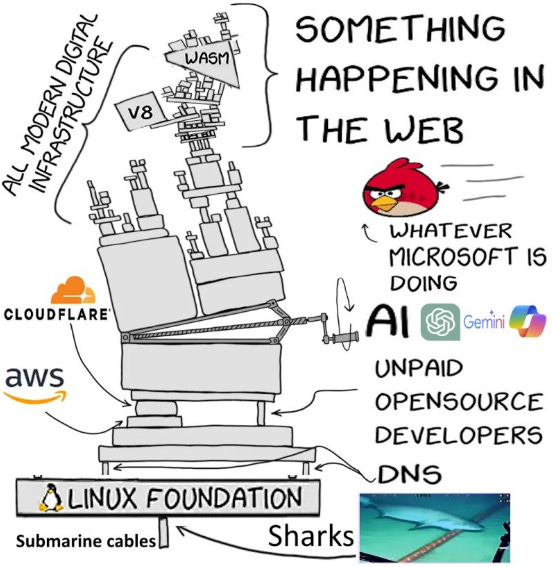

WASM for the JVM Is Gaining Momentum

WebAssembly is one of those standards that has been circulating in industry narratives for years like Death in Venice - everyone knows it’s about to take off, it’s just that the “any moment now” keeps getting postponed.

(Sorry for the slightly hermetic Polish literary joke - couldn’t resist.)

And yet, looking at what’s happening today in the JVM ecosystem, it’s hard to shake the feeling that WASM is finally starting to find its place - and in several interesting niches at once.

The most obvious signal is GraalVM, which is increasingly treating WebAssembly not as an exotic target, but as one of the first-class ways of executing code. WASM in Graal’s incarnation is not trying to replace the JVM or AOT in the style of Native Image — instead, it offers yet another secure sandbox that Java can interact with on its own terms.

In parallel, a completely different approach is emerging, represented by CheerpJ. This line of thinking doesn’t ask “how do we port Java cleanly to WASM?” but rather “how do we make existing JVM applications simply run in the browser?” — without rewriting, without porting, without months-long migrations. CheerpJ demonstrates that WebAssembly can act as a compatibility layer - something akin to a modern JRE for the web world. It’s a highly pragmatic vision, especially for old, heavy desktop applications that suddenly get a second life in the browser.

On top of that comes Kotlin, which for a long time has treated the web as a first-class platform rather than merely a “frontend to a backend.” In JetBrains’ latest plans, WASM is increasingly visible as a real alternative to JavaScript in places where predictability, performance, and consistency of execution models matter. This is not a mass movement yet, but the direction is clear: Kotlin/Wasm is not meant to compete with JavaScript in writing widgets, but in building serious web applications that don’t want to inherit the full baggage of the browser ecosystem.

The most interesting pieces, however, are projects that show WASM from the inside. One of my favorite spikes of the year is the story of porting the Chicory WebAssembly runtime to Android. It’s a great example of the fact that WebAssembly is not a magical format that solves all problems. Quite the opposite — it forces very deliberate thinking about memory, ABI, execution models, and host integration. And that’s precisely why it fits the JVM so well: a platform that has lived for decades at the intersection of high-level abstraction and hardcore runtime engineering.

Taken together, this paints an interesting picture. WASM in the JVM world is not a “new JVM” trying to replace bytecode or HotSpot. Instead, it’s another universal execution format that can be plugged in wherever isolation, portability, or execution in previously inaccessible environments is required. Browser, edge, sandbox, mobile - in all these places, WASM can serve as a natural bridge.

And perhaps that’s exactly why this time WebAssembly really does have a chance to take off. Not as a hype-driven replacement for everything, but as a missing puzzle piece. JVM, being the JVM, doesn’t rush into WASM with startup-style enthusiasm - it approaches it methodically, calmly, and with full awareness of its limitations. And Java’s history suggests that this is usually the best predictor of long-term success.

However we need to remember world looks a bit different nowadays.

TornadoVM Is having the time of its life

For years, TornadoVM was one of those projects everyone “had on their radar,” but few treated as anything more than an academic curiosity - fitting for a project coming out of the University of Manchester. Java on GPUs, FPGAs, and accelerators? It sounded like a future that was always one conference too far away. The year 2025 very clearly changed that picture. TornadoVM stopped being a promise and started to look like a technology that has genuinely found its place in the JVM ecosystem, addressing concrete needs of the platform.

One of the most symbolic signals of this shift was a personnel move. Juan Fumero, one of the leaders of the TornadoVM project and the public face of the BeeHive Lab at the University of Manchester, joined the Java Platform Group at Oracle. This is the moment when an experimental research project meets, directly, the team responsible for the future of OpenJDK. It’s hard to imagine a clearer sign that JVM acceleration is no longer a side topic.

The strongest signal of TornadoVM’s “entry into the real world,” however, turned out to be GPULlama3.java. Running LLaMA on GPUs without leaving the Java ecosystem, without writing CUDA, and without manual memory management is something that would have sounded like clickbait just two years ago. The 0.2.0 release of the project proved that TornadoVM is not only capable of handling simple kernels, but can also support real AI workloads.

What’s crucial here is that TornadoVM never tried to compete with GraalVM, CUDA, or OpenCL on the level of “who’s faster.” Its ambition was different: to let JVM developers think in terms of tasks and data, rather than threads, blocks, and registers. In this context, TornadoVM 2.0 (which I will cover more deeply in January) looks like the transition point from a research prototype to a platform. A more stable programming model, better integration with the JVM, real support for GPUs, CPUs, and accelerators - and, above all, less magic and more predictable contracts. This is exactly the moment when a project stops living only in academic papers and starts living in production repositories.

The most interesting question is no longer “does TornadoVM make sense,” but rather: when will we see its DNA in OpenJDK? Perhaps not as a ready-made framework, but as APIs, abstractions, and a direction for JVM evolution prepared for a world where the CPU is just one of many places where code runs.

Seen more broadly, TornadoVM fits perfectly into a moment in which Java is once again redefining its boundaries. Not by changing syntax, but by changing where and how code is executed. And perhaps for the first time in a long while, hardware acceleration in Java no longer looks like an experiment.

TornadoVM has truly come into its own.

BTW: We had a guest appearance post in the December about TornadoVM Architecture - I consider it the essential lecture for 2026 😁

Project Stargate Becomes Oracle’s New Darling

At first glance, Project Stargate looks like something completely outside our bubble. OpenAI, SoftBank, gigantic data centers, hundreds of billions of dollars, and a narrative straight out of AI geopolitics. It’s hard to imagine anything further removed from the JVM, GC, and JDK releases. And yet - if you look more closely - Oracle shows up in this story in a way that makes it entirely reasonable to talk about it right here.

In January 2025, OpenAI and SoftBank announced Stargate: a long-term project to build hyperscale computing infrastructure for AI, ultimately valued at as much as several hundred billion dollars. The goal is not a single data center, but a global network of facilities designed from the ground up for training and inference of large models. It’s an attempt to create an “intelligence factory” - infrastructure positioned as a strategic asset… all based on GPUs from Nvidia.

And this is where Oracle enters the picture, as a real operator and cloud provider. Oracle Cloud Infrastructure is meant to be one of the pillars of Stargate - both technologically and operationally. This is a very interesting turn, because for years Oracle was perceived more as a databases-and-enterprise-legacy company than as a player shaping the AI compute race. Stargate shows that this perception is becoming increasingly outdated.

From a JVM perspective, this is still very much a “side topic.” Stargate is not about Java, bytecode, or HotSpot, but about GPUs, networks, power, cooling, and decades-long contracts. At the same time, it involves the same company that owns the JavaScript trademark, develops OpenJDK, pushes Valhalla, Leyden, and Babylon, and makes enormous amounts of money on enterprise Java. Oracle is playing on several boards at once - and Stargate illustrates the scale of that game.

Project Stargate is a story about just how much the landscape around the JVM is changing. About how companies that spent decades building stable, boring IT foundations are now also players in the most capital-intensive and futuristic technology race of our time.

And even if the JVM stands a bit off to the side here, Oracle - somewhat atypically for itself - is standing very close to the center of the stage. It will be interesting to see how much of this we’ll start to notice over the coming year.

3. Major Releases

Spring Framework 7 and Spring Boot 4: A New Generation

November 2025 closed a very long chapter for Spring. Spring Framework 7 and Spring Boot 4 are the first releases that assume the market has already moved on. You can see this in every decision: Java 17 as the minimum baseline, optimization for JDK 25, and Jakarta EE 11 as the new normal.

There is also a very clear shift toward standardization instead of custom, homegrown solutions. The move to JSpecify as the default source of null-safety signals that Spring is no longer building its own micro-standards and is instead playing in the same league as OpenJDK, JetBrains, and the rest of the tooling ecosystem. This matters enormously for adoption in polyglot teams, especially where Kotlin and Java coexist in a single codebase.

Spring Boot 4.0, in turn, marks a moment of deliberate “slimming down” of the ecosystem. The removal of Undertow, RestTemplate (on the horizon), XML, JUnit 4, and Jackson 2.x clearly shows that anything blocking evolution will not be maintained indefinitely. At the same time, the modularization of spring-boot-autoconfigure demonstrates that Spring is taking startup time, security surface, and debuggability very seriously - precisely the areas that now determine platform choices in large organizations.

Against the broader market backdrop, Spring 7 / Boot 4 positions itself with remarkable clarity. This is not a framework for the “freshest experiments” - that role is increasingly taken over by Quarkus or Micronaut.

Spring remains the default enterprise JVM platform, but in a far more disciplined, modern, and coherent form than a few years ago, consolidating what has become the standard: Jakarta, modern JDKs, cloud-native operations, and deep tooling integration.

Spring Modulith 2.0 as the consequence of a single, coherent vision

Spring Modulith 2.0 is particularly interesting not only because of what it introduces, but because of who stands behind it. This is still the same line of thinking that Oliver Drotbohm has been developing for years - the author of Spring Data, the initiator of jMolecules, and one of the most consistent voices in the Spring world when it comes to connecting domain architecture with framework practice. Modulith is therefore not a new idea coming “from the side,” but the culmination of concepts that have been maturing in the ecosystem for over a decade.

For years, Drotbohm has argued that the biggest problem of enterprise systems is not a lack of frameworks, but a lack of enforceable boundaries. Domain-Driven Design offered excellent concepts, but weak tools for enforcing them. Spring provided immense flexibility, but made it just as easy to abuse. jMolecules was the first attempt to dress architecture in code - to give names, stereotypes, and semantics to what previously existed only as diagrams. Spring Modulith is the natural next step: moving that semantics into the very heart of the Spring runtime.

Spring Modulith 2.0 stops pretending that modularity is a matter of developer goodwill. Integration with jMolecules 2.0 changes the rules of the game — DDD stereotypes such as @Aggregate, @Repository, or @ValueObject, which used to be comments for humans, now become contracts enforced by Spring. The framework understands your domain: it knows that an aggregate should not directly access another aggregate, that a repository operates on aggregate roots. Violations of module boundaries no longer surface in code reviews, but as red builds. Module boundaries stop being lines drawn in the sand on a wiki and become walls guarded by the framework - move a class between modules and you immediately see what you broke, instead of discovering it in production.

Spring Modulith 2.0 arrives at the perfect moment. The market is clearly moving away from unreflective microservices enthusiasm, but at the same time has no desire to return to unstructured monoliths. The so-called “modular monolith” thus becomes a conscious architectural choice. Through Modulith, Spring shows that it is possible to build systems that are coherent, modular, and operationally simple - without breaking everything into a mesh of services.

Spring AI - Spring positions itself as a system layer for LLM-Based Applications

By 2025, it was already clear that integration with LLMs is not the problem of a single library, but of the entire application architecture — from configuration and observability to security and model lifecycle. Spring AI emerged precisely in this gap. It very quickly stopped being a “wrapper around the OpenAI API” and began to play the role that “classic” Spring has always assumed during major technological shifts: normalizing chaos. And the release of Spring AI 1.0 in May 2025 - after more than a year of intensive development - officially closed the experimentation phase.

What matters most is what Spring AI does not try to do. It does not compete with LangChain or purely agent-oriented frameworks. Instead, it assumes that an LLM is just another external system — like a database, a broker, or a file system — and as such should be handled consistently with the rest of a Spring application. Concepts such as ChatClient, Advisors, memory, and tool calling were designed to fit existing configuration, transactional, and testing models, rather than bypass them.

In this way, against the current landscape, Spring AI positions itself as an enterprise-grade glue layer. For teams that already use Spring Boot, Spring Security, Actuator, and Micrometer, entering the world of LLMs does not require rebuilding their mental model of the application. This is a massive adoption advantage — especially in organizations where experiments must very quickly transition into maintenance, audit, and scaling mode… particularly if those organizations already use Spring. And since many do, having such a “default” from a familiar provider genuinely simplifies things.

Langchain4j 1.0: A Java-Native Framework for LLMs

Spring AI was not the only JVM project to reach a 1.0 milestone in 2025. A few months earlier, in February, Langchain4j crossed the same threshold — and while both frameworks address LLM integration, their philosophies differ significantly.